We work closely with this broad mix of partners to test new drivers, monitor health characteristics over time, and make Windows and our ecosystem more resilient architecturally. Our goal is to ensure that all the updates and drivers we deliver to non-Insider populations are validated and at production quality (including monthly optional releases) before pushing drivers broadly to all. Within such complexity, this still means that some combinations and configurations in the real world will require Microsoft or our partners to make adjustments. In this blog, part of our series on the Windows approach to quality, Tom Frankum from our Silicon, Graphics and Media team will provide more detail about the work we do to improve Windows driver quality.

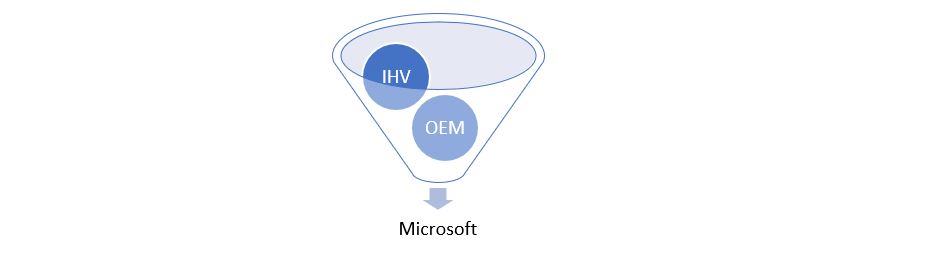

The driver distribution chain

Drivers are tested extensively through a process that involves many companies. The first wave of testing is conducted by the independent hardware vendor (IHV). When an IHV—such as Intel, AMD or NVIDIA—creates a hardware component, it puts the hardware through significant testing that typically includes validating OS compatibility using the Windows Hardware Lab Kit (Windows HLK). The Windows HLK is a test framework designed to help IHVs automate the process of testing hardware devices for Windows, and meet the requirements for certifying their devices through the Windows Hardware Compatibility Program. When customers download drivers from an IHV’s website, they are typically getting a driver that has met the IHV’s quality bar as well as basic Windows 10 operating system compatibility standards.

Next in the chain is the original equipment manufacturer (OEM), who tests the driver on each configured system they offer. An OEM—such as Dell, HP, Lenovo or Surface—matches the new driver to the various devices it ships and completes its own battery of tests. Feedback is shared with the IHV and may result in further driver updates. Validated drivers are then released via the OEM’s website or update tools, targeting the specific devices that the OEM believes have passed their quality bar.

Last in the driver distribution chain is Microsoft. IHVs and OEMs submit drivers to Microsoft, and we flight these drivers within our engineering system and, eventually, to Windows Insiders. If the driver performs well, we release it to Window Update (WU) for Windows customers to download automatically. If the driver doesn’t meet our standards, we reject the driver and ask the IHV or OEM to make updates that will improve how the driver works with Windows.

Microsoft processes more than 100 drivers a day submitted from IHVs and OEMs and many more are posted to IHV or OEM websites every day. In fact, there are several million active drivers in the Windows 10 ecosystem, which makes it very complex to evaluate the changes that occur over time. 2018 has been a particularly busy year because we made changes to Windows in response to new chipset-level security discoveries, and these changes necessitated an unprecedented number of updates to drivers and firmware. As a result, everyone in this distribution chain has been busy updating and testing in order to release secured drivers and firmware to the world.

Measuring and detecting driver quality

Improving driver quality is a constant focus for Microsoft and our partners. We don’t work on it in isolation, but as a combined effort across the ecosystem. Our goal is to deliver a great experience across all hardware for Windows customers every day. If there is an issue with a driver, our goal is to detect that quickly, stop customers from being impacted, then develop a fix as fast as possible for our joint customers. We use a combination of diagnostic data, feedback and other listening systems to detect when customers experience issues. We analyze a variety of metrics every day to assess and understand quality.

For example, one of the metrics we study is blue screens. We know this is an incredibly disruptive event; everything comes to a halt and the PC reboots after collecting important crash information.

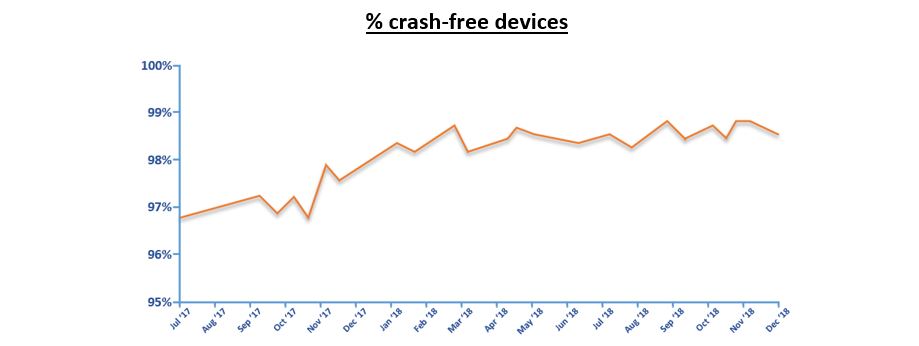

Internally, we use a metric called “crash free,” which is defined as the percentage of machines in a population that experience no driver crashes during a given window of time. For the crashes we do see, we stack rank them based on the number of machines impacted, partner with IHVs to fix, and work with OEMs to automatically distribute updates to end users. As a result, the percentage of crash-free Windows 10 devices has increased from less than 97 percent to greater than 98 percent[i] over the past two years.

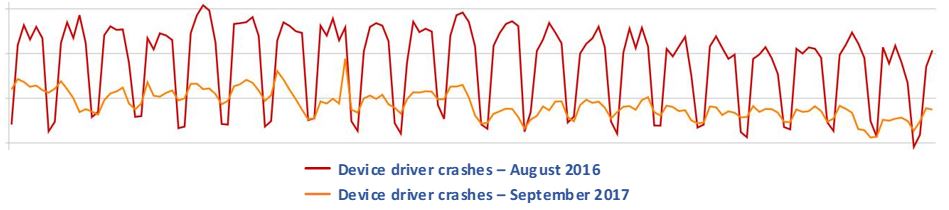

Fractions of a percentage point matter when it comes to driver crashes, and we are striving to achieve an even higher crash-free rate for Windows 10 devices. To do this, we isolate drivers with higher than standard crash rates, work with our partners to adjust, re-validate, and continually measure the overall reliability. Driver by driver, we improve the overall reliability of Windows 10. The graph below shows one specific driver, where we followed this process and saw significant improvement from the crash rates in red (August 2016) to the performance in orange (September 2017).

Preventing conflicts

Driver conflicts arise when something is wrong with a specific driver, such as incompatibility, preventing Windows from properly utilizing associated hardware. During the rollout of a new Windows 10 feature update, we carefully monitor quality and feedback signals, including from driver quality to ensure the best possible update experience. If we detect that a device may have an issue, such as a driver incompatibility, we will not install the update until that issue is resolved by blocking that device from updating. This means that Microsoft will not offer an operating system update to devices with the combination of hardware and driver version that is at the root of the conflict. Instead, we wait until the issue has been fixed, re-tested and fully deployed, and then remove the block. We recently started sharing more of the details about these blocks on the Windows 10 update history page. An example of past issues with associated blocks can be seen here.

Improving quality through architecture

While we’ve seen improvements over time, we know there is more work to do. For example, we are working with our hardware partners to remove the complexity in Windows drivers and, in some cases, eliminate the need for third-party drivers altogether by creating a ”class driver” that works for all hardware in a category. Where class drivers are not an option, we are working with hardware partners and sharing quality data to reduce the number of driver variations that get released to customers. This collaborative approach brings more eyes to every driver prior to release and, in the end, yields fewer drivers in active circulation and a higher quality for each driver that is released.

We will continue to work closely with our partners across the industry to detect the issues customers experience, remedy those issues quickly and, ultimately, work to deliver the highest quality drivers to our customers possible. We will be sharing more soon in our Windows approach to quality blog series.

[i] Across a broad range of devices and Windows 10 operating system versions.

…